What Voyager Detected at the Edge of the Solar System

In 1977, NASA launched the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft to explore planets beyond Neptune and to investigate their positions within the solar system. Although initially designed for a 5-year mission, these spacecraft have far exceeded their expected lifespan and are still operational, sending data from interstellar space, about 24 billion kilometers away.

Voyager 1 and 2 are more than just scientific instruments; they represent human curiosity, boldness, and endurance. Despite using outdated technology, such as computers with memory less than today’s car keys, they were engineered for longevity with energy from plutonium-238 radioisotope thermoelectric generators. This design allows them to continue functioning until at least 2025.

The spacecraft were not only built for their original mission but were also upgraded for extended missions. Equipped with various scientific instruments and backup systems, both Voyagers have maintained their functionality over time. They use plutonium-238 generators, providing enough power to sustain their operations throughout their long journeys.

Voyager 2 was launched on August 20, 1977, from Cape Canaveral, Florida, and Voyager 1 followed on September 5, 1977. Voyager 1 was designed to travel faster and thus overtook Voyager 2, arriving at Jupiter on March 5, 1979. The images sent back from Jupiter by Voyager provided detailed insights into the planet, revealing dynamic features such as its atmosphere and rings, which were previously unknown.

Exploring the Solar System Through the Voyager Mission

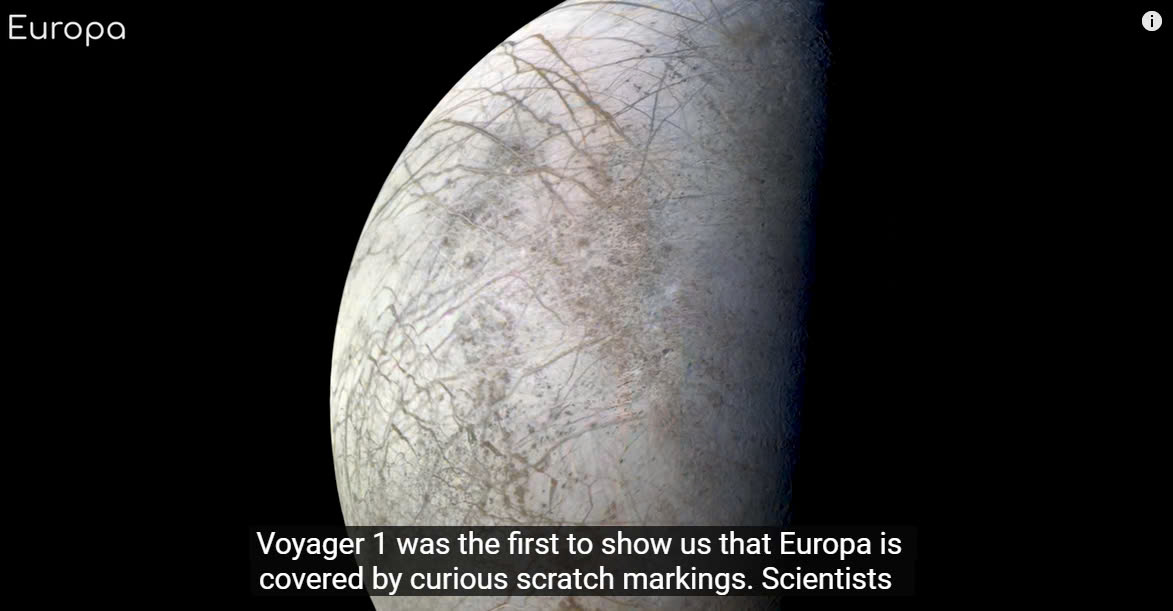

**Io and Europa**: When the Voyager spacecraft arrived at Jupiter in 1979, we discovered that Io, one of Jupiter’s moons, had intense volcanic activity, contrary to previous expectations of a crater-covered moon. Io had lava flows from less than 1 million years ago and is known as one of the most geologically active places in the solar system. Voyager also found that Europa has a surface of ice with crack patterns and may have an ocean hidden beneath the ice.

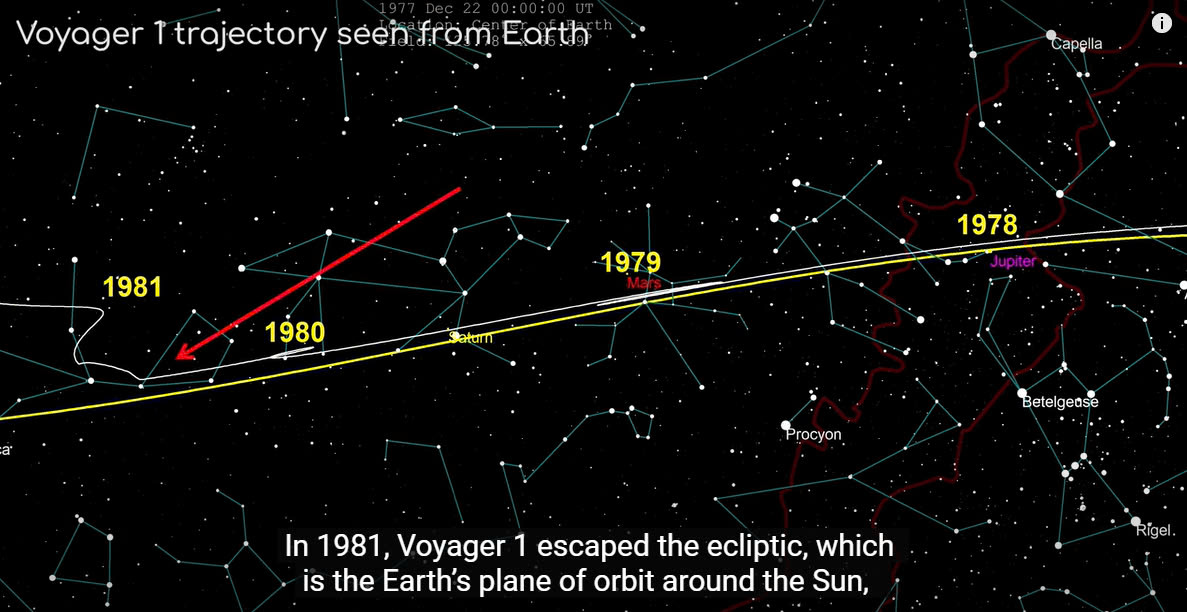

**Exploring Saturn**: By November 1980, Voyager 1 reached Saturn and revealed that its rings were not just five large rings but hundreds of thin ringlets. Voyager also discovered the G-ring and provided details about the F-ring discovered earlier. The images revealed strange features like “ghostly spokes” on the B-ring and showed that Saturn is losing its rings due to gravity pulling them into the planet. Voyager also found three new moons, increasing Saturn’s total to 17.

**Exploring Uranus**: In January 1986, Voyager 2 approached Uranus and found that the planet has a magnetic field tilted 59 degrees from its rotation axis, which was a major surprise. Voyager 2 also discovered two new dark rings and 11 additional moons of Uranus, bringing the total to 16.

**Exploring Neptune**: By August 1989, Voyager 2 reached Neptune, discovering extremely high wind speeds and a massive storm called the “Great Dark Spot.” The spacecraft also detected incomplete ring arcs around Neptune and six new moons. Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, was found to have a fractured surface with geysers and a pinkish nitrogen ice cap.

**Final Moments**: Before leaving the solar system, Voyager 1 took the famous “Pale Blue Dot” photo from about 6 billion kilometers away in 1990, emphasizing the tiny size of Earth in the vast universe.

Voyager Probes and Their Discoveries

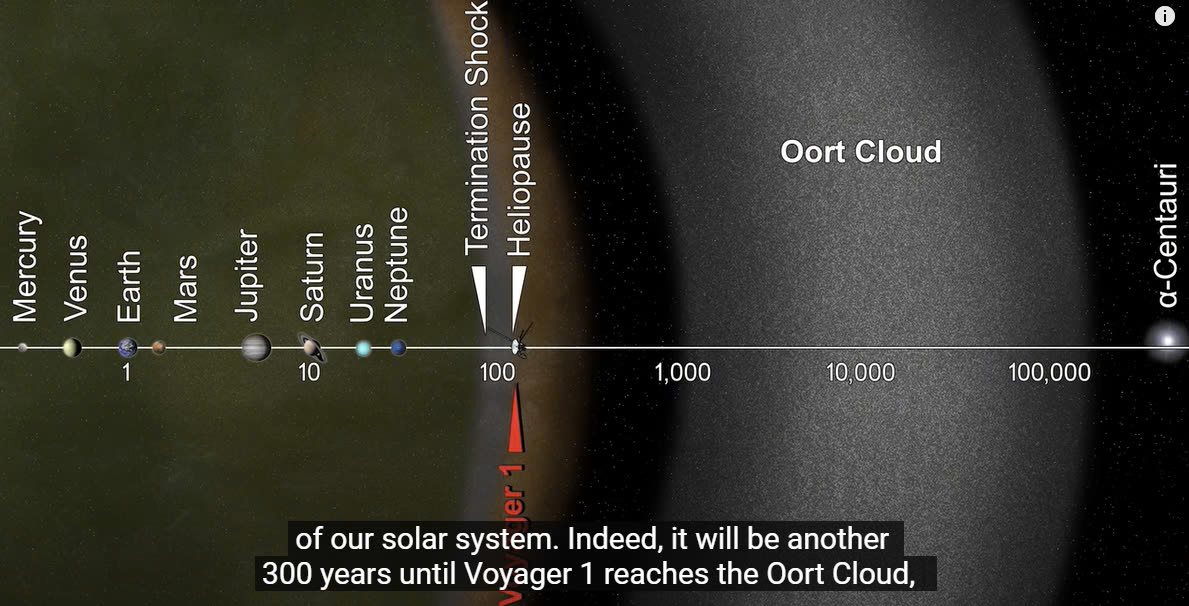

**Journey Beyond the Solar System**: After leaving the termination shock, Voyager probes enter the heliosheath, where the solar wind slows down and becomes denser. They eventually reach the heliopause, the boundary between the heliosphere and interstellar space. However, the solar system extends further, with Voyager 1 taking 300 years to reach the Oort Cloud and another 30,000 years to exit it.

**Discoveries in the Heliosheath**: Voyager probes found that the Sun’s magnetic field creates ripples known as the heliospheric current sheet. These ripples form magnetic bubbles at the termination shock, revealing that the heliosheath’s boundary is more complex than previously thought.

**Voyager 1’s Milestone**: Voyager 1 became the first man-made object to enter interstellar space on July 25, 2012, traveling at 540 million kilometers per year. It crossed the heliopause about 120 Astronomical Units from the Sun, confirming that earlier models of the heliopause’s location were incorrect.

**Unexpected Findings**: Initially, NASA was unsure if Voyager 1 had truly left the solar system due to unexpected data about the magnetic field. It took almost a year for confirmation.

**Voyager 2’s Journey**: Voyager 2 followed on November 5, 2018, crossing the heliopause at the same distance from the Sun as Voyager 1. It also showed no change in the magnetic field, challenging previous models.

**Technical Issues**: In 2022, Voyager 1 experienced data issues due to a malfunctioning computer, but the problem was fixed by switching to a working computer. Further issues with another computer arose in November 2023, which were resolved by mid-2024.

**Voyager 2’s Communication Challenge**: A slight misalignment in 2023 caused Voyager 2 to lose contact with Earth, but a signal from Australia helped reestablish communication.

**Future of the Probes**: The Voyager probes will eventually stop transmitting data. Voyager 1 will likely drift toward a star in 40,000 years, and Voyager 2 will pass near another star in 1.7 light-years. These probes will outlast Earth and symbolize human exploration.

**The Golden Record**: Each probe carries a Golden Record with information about Earth, including images, sounds, and greetings in various languages, meant for any potential extraterrestrial life.

**Conclusion**: As we bid farewell to these spacecraft, the Voyager Mission remains a significant achievement in our quest to explore the universe.